MarineLives

Our volunteers

MarineLives is a collaborative volunteer driven project. The project started as a spinoff from a National Archives hackathon in early 2012. We are dedicated to the collaborative transcription, linkage and enrichment of primary manuscripts from the High Court of Admiralty, 1650-1669 (with some excursions into data from the 1630s and 1640s).

Currently, we have just over 10,000 images available (29 GB) and 11,400 pages of full text transcriptions on the MarineLives wiki.

Please contact us if you would like to learn more about this summer's project and how you can help, or if you would more generally like to learn about the work of MarineLives volunteers.

We would like to recognise and thank all those who have contributed to our project (in alphabetical order), whether as volunteer transcribers, annotators, commentators, advisors, interviewees, or PhD Forum participants.

Dr Aquiles Alencar-Brayner

Dr Roberta Anderson

Deborah Ashby

Rachel Bates

Rowan Beentje

Dr Richard Blakemore

Lior Blum

Katie Broke

Dr James Brown

Dr Andy Burn

Elio Calcagno

Michelle María Early Capistrán

Rachel Carter

Giovanni Colavizza

Dr Justin Colson

Thierry Daunois

Dr John Davies

Thomas Davies

Jonathan Dent

Melvyn Dresner

Dr Stuart Dunn

Professor Kai Eckert

Bob Egan

Dr Charlene Eska

Louise Falcini

Emilie-Jane Farrimond

Dr Janet Few

Sara Fox

Dr Ian Friel

Dr Perry Gauci

Marja Geesink

Adam Georgie

Jaap Geraerts

Jamie LH Goodall

Guy Grannum

Colin Greenstreet

Francesca Greenstreet

Adam Grimshaw

Karen Gunnell

Yerevag Hagopian

Dr Liam Haydon

Phillipa Hellawell

Dr Helmer Helmers

Dr Philip Hnatkovich

Rachel E. Holmes

Dr Jenni Hyde

Steve Ives

Alex Jackson

Stefan Jäggi

Elin Jones

Sue Jones

Ross Keel

Dr Patricia Keller

William Kellett

Sara Kerr

John Kuhn

John Layt

Sjoerd Levelt

John Levin

Grace Mallon

Simon Marsh

Dr Alan Marshall

John Miller

Anne Mills

Kate Morant

Matthias Müller-Prove

Professor Steve Murdoch

Dr Shavana Musa

Harriet Richardson

Gordon O'Sullivan

Katherine Parker

David Pashley

Dr Cathryn Pearce

Nga Phan-Bellis

Professor Simone Paolo Ponzetto

Jo Pugh

Patrizia Rebulla

Bethan Reynolds

Daniel Richards

Andrew Richens

Dr Mia Ridge

Dominique Ritze

Dr Gavin Robinson

Margaret Schotte

Steven Schrum

Laura Seymour

Ida Sjoberg

Edmond Smith

Daniel Stewart-Roberts

Chad Stolper

Roger Towner

Alexis Truax

Dr William Tullett

Oliver Turner

Dr Brodie Waddell

Samuel Watson

Jill Wilcox

Royline Williams-Fontenelle

Ad van der Zee

Dr Kathrin Zickermann

Dr Suze Zijlstra

Cäcilia Zirn

and the ever helpful but anonymous @_mapnut

Summer challenge, 2017: How to make money in C17th commercial shipping?

This summer the MarineLives project team is looking at the drivers of profit and loss in C17th commercial shipping. We will publish as we go and welcome comments, contradiction, and offers of help and data.

Early results from our work

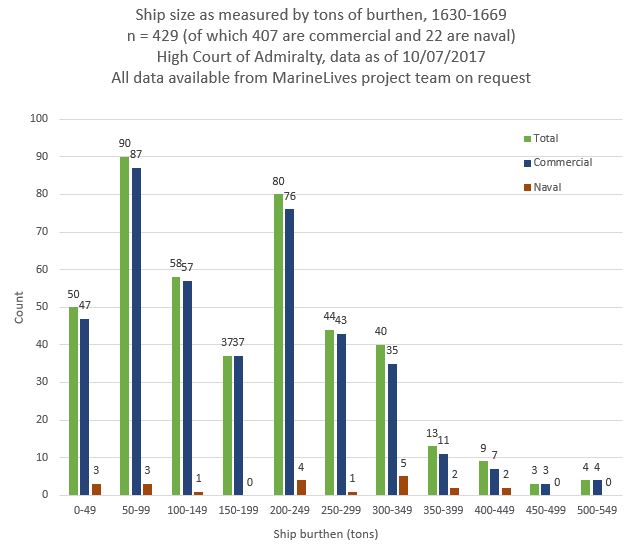

There are two clear peaks in the data for commercial ships - the first peak is in the 55 to 99 ton burthen category and the second peak is in the 200 to 249 ton burthen category.

Admiralty Court witnesses refer to ships of 50 and 60 tons as "small" and ships of 300 to 350 tons and above as "large". The smallest ton burthen category in our analysis (1-49 ton burthen) contains lighters, some barges and hoys, and other small river and coastal vessels.

We would be interested in our readers comments on these data.

Are the averages and ranges in the same ballpark as data in the hands of our readers, both from the C17th and earlier and later periods?

What can you tell us about the use to which these different types of commercial vessel were put?

Riverine versus coastal versus longer distance use? Cargo types? Crew and gun levels? Rental rates?

Our current dataset for tonnage based freight rates consists of thirty-six observations for a range of fine, coarse and bulk goods.

They cover short transportation distances, such as Kingsale in Ireland to London through medium distances, such as Cyprus and Scanderoone to London, and long distances, such as Bantam in the East Indies to London.

The outbreak of war had significant impact on tonnage based freight rates. For example, war between England and the United Provinces in the early 1650s, sharply pushed up freight rates on galls and cotton wool from the Eastern Mediterranean to London.

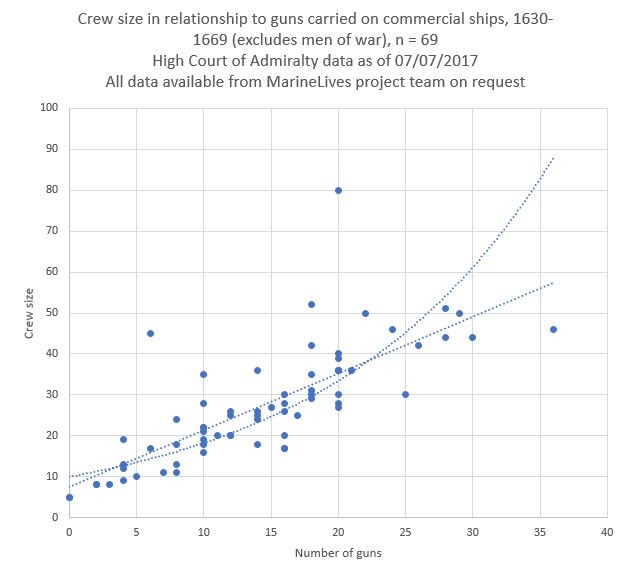

Driving the higher freight rates during times of war was the need to have higher manning levels on ships, higher mariner wages per man, and higher gun intensity per tun of ship burthen.

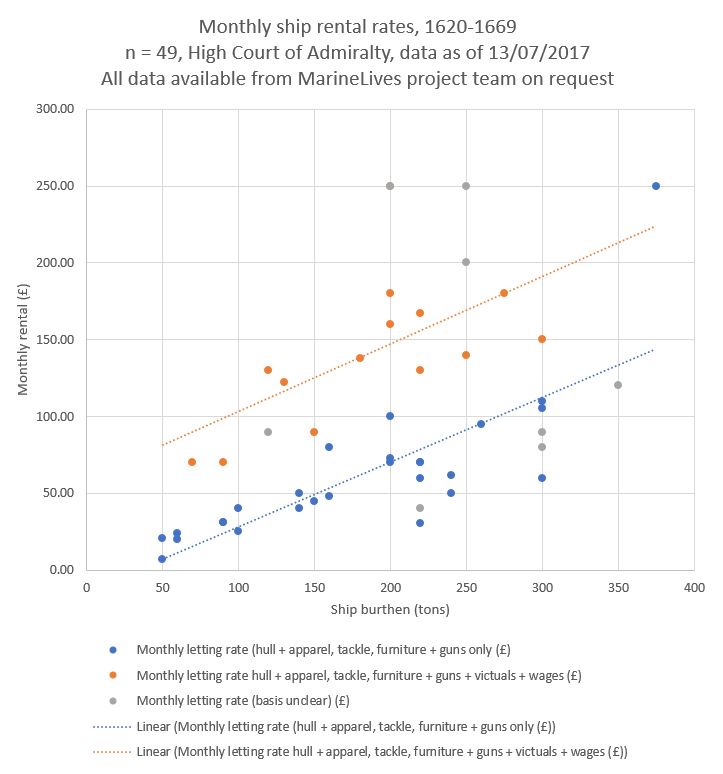

Our current dataset for monthly rentals consists of forty-nine ships.

Twenty-seven of these are rental rates for hull plus apparel, tackle, furniture and ordinance, but excluding provisions and wages, which were to be paid directly by the renting agent.

Fourteen are rental rates for hull plus apparel, tackle, furniture and ordinance and including provisions and wages, which were to be paid by the ship owner and recovered through the monthly rental. We know the monthly rental rates for three of these fourteen also on the basis of excluding provisions and wages.

Finally, we have eight rental rates for which it is unclear on what basis the rentals were contracted.

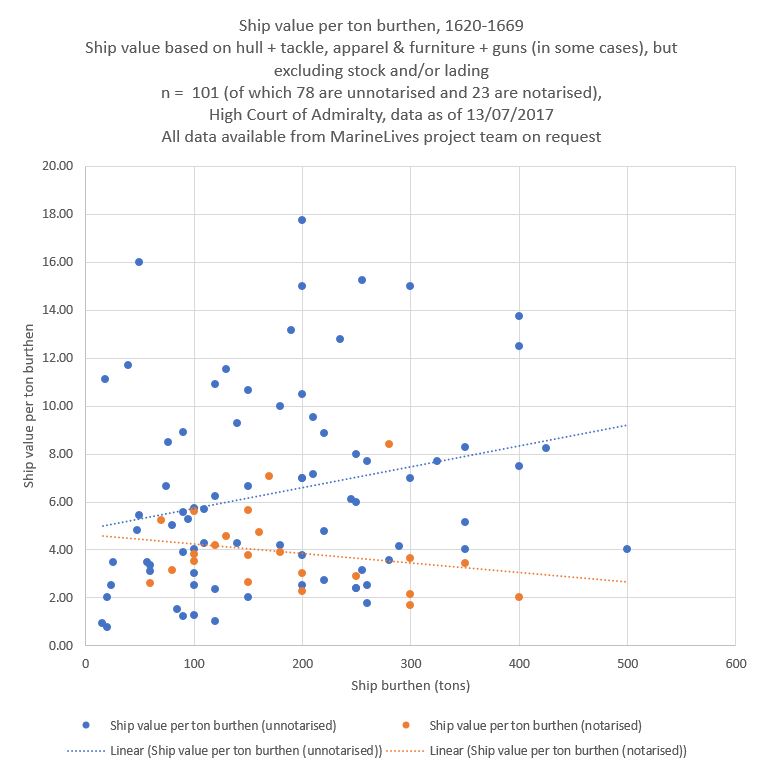

Our current dataset consists of one hundred and one ships, of which seventy-eight ship values are unnotarised and twenty-three ship values are notarised. Notarised values are lower (average = £3.90 per ton of ship burthen) comparised with unnotarised vales (average = ££6.40 per ton of ship burthen). Notarised values show a significantly tighter range around the average and mean than do unnotarised values.

We are working on disambiguating our data, but believe the differences in averages, means and range are due to the unnotarised data being more mixed in nature. Specifically, unnotarised data tends to be generated from witness statements of ship value following the seizure of a ship. We have excluded witness valuations of ships where it is clear that the outward, interim or return lading of the ship has been included in the witness valuation. Similarly, we have excluded witness valuations of ships where it is clear that an outward monetary stock has been included in the valuation.

However, even with these exclusions, the valuation of ships during their voyage usually includes some portion of the provisions carried on board the ship. If a seizure is early in a planned long voyage, these provisions could amount from anything between six and twenty months.

Moreover, the valuations of ships during their voyage will include some attribution of value to the refitting and setting out of a ship prior to a voyage, which can vary in the case of the hull from repairs to full graving and caulking or even resheathing, and in the case of the apparel, tackle and furniture, can include totally new provision of sails, rigging, blocks and other materials. Witnesses appear to make some allowance for the wear and tear of a ship on a long voyage and sometimes comment on this when giving their unnotarised valuations in their depositions in the High Court of Admiralty.

We plan to add ship inventories to our database, sourced from High Court of Admiralty appraisements of seized ships. These inventories will provide detailed breakdowns of the value of the physical components of ships in this period.

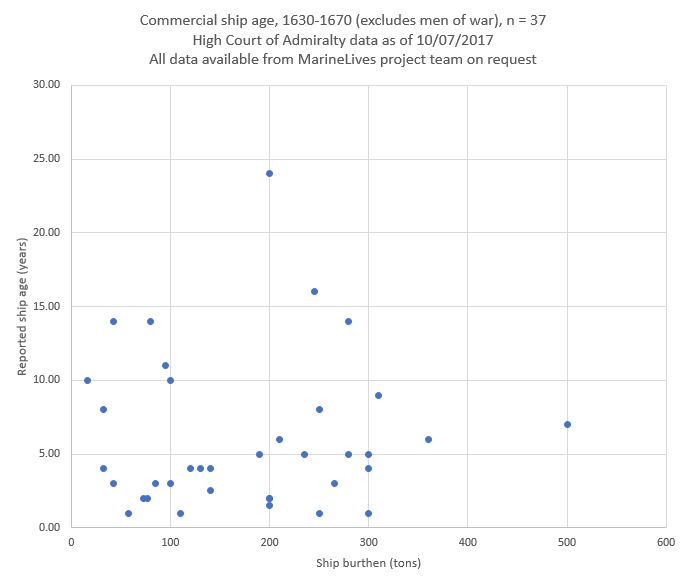

The average age of ships for which we have age and tonnage data is 6.1 years (n=37), whereas the average age of ships for which we have age data accurate to the year for which we have no tonnage data is 7.1 years (n=41).

Dr Ian Friel has shared with us a summary of data from his unpublished survey of High Court of Admiralty inventory documents from the 1580s. His data are for a period forty to eighty years earlier than our own High Court of Admiralty data. Ian's survey found ages for thirty-nine ships, with an average age of nearly fifteen years and twenty-nine of them of ten years or more in age.

Comparison of textual and numerical data for 1630-1670, with the bulk of the data from the 1650s, suggest Admiralty Court witnesses regarded ships aged between zero and five years as "new" and ships of fourteen years and above as "old".

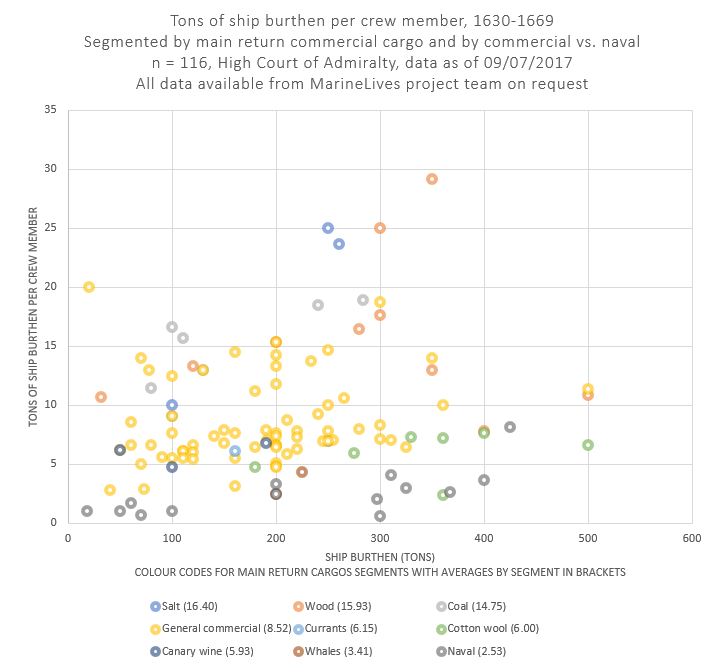

The average crew size for the larger dataset is 47.3, including six exceptionally manned men of war with 275 or more men per ship (n = 172). The average crew size for the smaller dataset, where we have crew number and ship tonnage is 36.5 (n=116).

We are in the process of analysing these commercial data by geography and by commodity as well as by year to look for patterns within the commercial data.

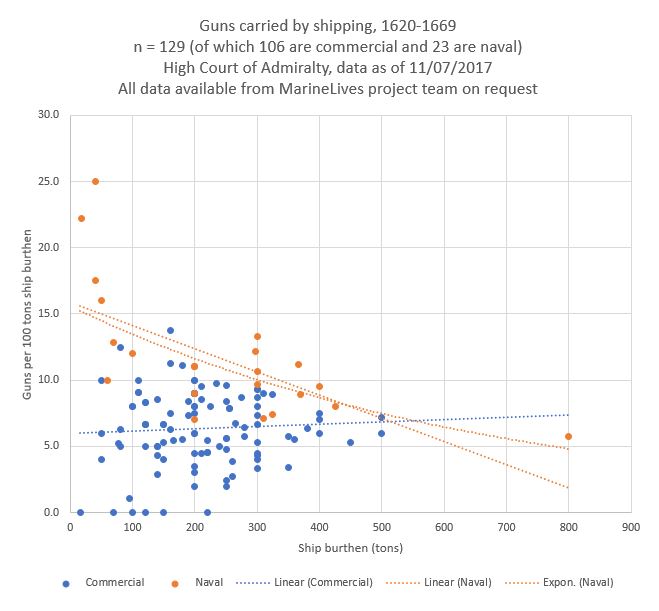

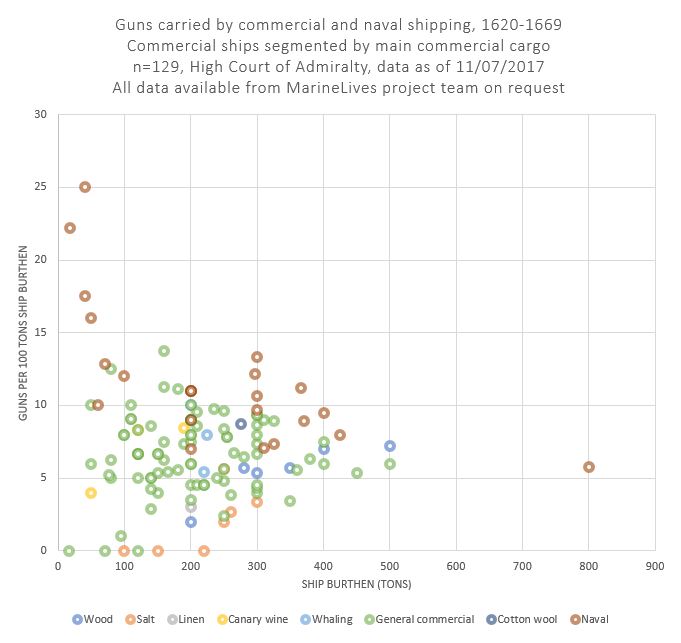

Amongst the naval ships (a category which includes both ships in the immediate service of a state as well as private men of war under commissions from a state), there is a clear pattern for smaller ships to be particularly heavily gunned.

Commercial ships carrying salt had few if any guns, in contrast to ships carrying Canary wines or cotton wool as their main return cargos.

This is likely to be driven by the low manning levels on salt ships per ton of burthen. Low manning levels meant that there were fewer people available to man guns.

We are looking at relative freight rates for salt, Canary wines and cotton wool, and at sale prices for different commodities, to see if these also drove gun levels.

Coal ships are also likely to have had few if any guns. However, most of the coal ship cases in High Court of Admiralty data concern collisions, resulting in court cases which do not ask about guns. Whereas, most of the salt ship cases in the High Court of Admiralty data concern seizures, and elicit Court cases in which gun intensity is relevant and asked about.

As we dig further into the general commercial category, we should be able to allocate a good portion of these to specific commodity groups and thus be able to improve our analysis of the drivers of guns mounted on commercial ships

The average gun number for just men of war is 22.4 (n=2). The average gun number for just commercial ships is 12.8 (n=137). Our sample of commercial ships where we have tonnage as well as gun number (n=69) has a slightly higher average gun number than for all commercial ships, where only gun number is known.

The commercial gun number average overestimates the gun carrying propensity of commercial ships, since there is a systematic tendency not to report absence of guns from smaller vessels (vessels of thirty to sixty tons burthen). Many of these vessels, particularly those involved in coastal trade or fishing, as hoys, busses and ketches, would not have carried guns.