Difference between revisions of "Impressment"

Olivertanner (Talk | contribs) |

Olivertanner (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

| − | Costello, Ray Black Salt. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2012,p. xvii. | + | Costello, Ray ''Black Salt''. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2012,p. xvii. |

| − | McLynn, Frank Crime and Punishment.London: Routledge, 1989, p. 61. | + | McLynn, Frank ''Crime and Punishment''. London: Routledge, 1989, p. 61. |

| − | Brandon, Pepijn and Karwan Fatah-Black ‘For the Reputation and Respectability of the State’.In: Building the Atlantic Empires, Boston: BRILL, 2015,pp. 84-104. | + | Brandon, Pepijn and Karwan Fatah-Black ‘For the Reputation and Respectability of the State’.In: ''Building the Atlantic Empires'', Boston: BRILL, 2015,pp. 84-104. |

| − | Davies, J. D. Pepys Navy: Ships, Men and Warfare. London: Seaforth Publishing, 2008, p. 112. | + | Davies, J. D. ''Pepys Navy: Ships, Men and Warfare''. London: Seaforth Publishing, 2008, p. 112. |

| − | Fury, Cheryl A. Social History of English Seamen. London: Boydell Press, 2011, p. 273. | + | Fury, Cheryl A. ''Social History of English Seamen''. London: Boydell Press, 2011, p. 273. |

| − | Denver, Brunsman ‘Men of War: British Sailors and the Impressment Paradox’. Journal of Early Modern History, 14 (1/2), 2010, pp. 9-44. | + | Denver, Brunsman ‘Men of War: British Sailors and the Impressment Paradox’. ''Journal of Early Modern History'', 14 (1/2), 2010, pp. 9-44. |

| − | Little, Andrew R. ‘British Seamen in the United Provinces during the seventeenth century Anglo Dutch Wars: the Dutch Navy – a preliminary survey’. In: Brand, Hanno Trade, Diplomacy and Cultural Exchange, Torenlaan: | + | Little, Andrew R. ‘British Seamen in the United Provinces during the seventeenth century Anglo Dutch Wars: the Dutch Navy – a preliminary survey’. In: Brand, Hanno ''Trade, Diplomacy and Cultural Exchange'', Torenlaan: Uitgeverij Verloren, 2005, pp. 75-92. |

| − | + | ||

Revision as of 19:04, June 2, 2016

Impressment and the Anglo Dutch War

Impressment caught my eye by chance, mentioned in a book I was reading for my potential dissertation topic on highway robbery, in which a highwayman frees press gang prisoners. Unaware of the extent of impressment, and anything beyond the most basic definition of it I decided to look into it in more depth, and attempt to garner what people really thought of it.

In this article I will go into detail on the definition of impressment and societies views of it, before linking it to the Anglo Dutch War.

Impressment was the legal act in which a ship forcefully rounded up a number of men of seafaring age (18-60) through the use of a group of men called a press gang and made them work on their ships for at least a year, or until the next war ended. Impressment was extremely unpopular, as men rounded up had no choice in the matter, the Royal Navy also had low wages and terrible conditions because it did not need to compete for employees like the merchant navy did, thanks to press gangs.

Impressment was not limited to just British sailors either, in times of war, black slaves were taken from the Caribbean or directly from Africa to work on British ships as impressed men. Even once the slave trade had finished many slaves were ‘freed’ only to be forced to serve for a period of time in the Royal Navy. White man were rarely happy with this situation, as it meant that they were on the same level as a black man - it against their way of life that a ‘white British man with ‘exquisite emotions’ should not be governed like a black slave’. When there was an increase in free black men living in England towards the late eighteenth century these men were also rounded up by press gangs.

The MarineLives websites provides a wealth of information on slavery, in a number of depositions treating them as commodities such as sugar, throughout HCA 13/71, for example. The website also provides a number of examples of wills, such as from Nathaniell Withers and James Kendall that mention slaves which are written as being passed onto their relatives.

Due to dangers in having a permanent standing navy (such as the risk during storms),impressment was only used sporadically before the standing navy’s enforcement in the second half of the seventeenth century. However impressment had been around for centuries before this, based upon the Feudal notion that if necessity called, all men could be called up to serve their King. Before this fleets were generally only gathered as a short term solution, which is why impressment wasn’t overwhelmingly objected against by British society. Impressment was seen as necessary for the British Navy because Navy recruitment struggled enormously, especially during wartime, when the Navy’s low wages simply weren’t worth the immense risk of death whilst at sea; in spite of a number of Parliament debates, the government frequently sided on the side of impressment, due its war time importance in defending the realm.

Press gangs were indiscriminate, not only did they recruit from all social classes, but they also often accidentally picked up men simply in the wrong place at the wrong time – 5000 farmers were reported to be in the navy in 1653. Although this seems like a horrific situation, press gangs usually only focussed on maritime areas to ensure that they mostly only took seafaring men; the community also quickly realised what was happening, and either hid men between the ages of 18 and 60 in houses or further inland so that they could avoid the press gang. Merchant vessel owners would also often bribe press gangs not to target their seamen. Due to these reasons press gangs were often extremely unsuccessful – one press gang for the Hound, in Ipswich, 1664, only found 9 men, of the 150 they were supposed to ‘recruit’.

Impressment was extremely unpopular,not only did men hide, but there were also regular riots attempting to free press ganged men, such as in 1666 in Deptford.

Davies humorously emphasises that the very first mention of a cricket bat being used as a weapon is from a description by John Balthorpe from during a riot trying to free press ganged men. There is also one account of two highwayman gaining popularity by attacking a press gang and freeing 30 would be sailors.

Brunsman writes that the crucial reason for the continuation of impressment was simply that sailor opposition did not seriously harm the navy, and seemed to have very little impact at all, he goes on to argue that although seamen went to great lengths to avoid impressment, because naval punishments were so severe, seaman would be relatively compliant once aboard. Though desertion rate was often between 7% and 10%, this was often less than European countries that hadn’t enforced impressment, and in saying this, there is evidence that by trapping sailors in debt European nations, such as the Dutch, would implicitly impress sailors.

Although most accounts of the navy emphasise it’s unpopularity with sailors above anything else, many people seemed to volunteer in peace time, and went on to serve for decades, escaping menial employment, domestic problems or prosecution for adventure, persuaded by bounties and lump sum wages, therefore often impressment was simply unnecessary. And even during war it was very rare for a majority of a ship’s crew to be impressed. Davies believes that, seeing as the percentage of impressed men varies dramatically ship to ship, people must have known the reputation of a ship’s captain, and either volunteered or were impressed accordingly. Therefore one can tell the popularity of a captain by the percentage of impressed men on his ship.

Not to say that impressment was ever popular however, Fury writes that it ‘deprived [seamen] of economic freedom’, jeopardising the family wellbeing and also spreading disease and death, as impressment stopped ship owners having to worry about job satisfaction. Though Samuel Johnson (himself impressed twice), accepted that those who went into the seafaring trade in doing so accepted all aspects of the trade, including the risk of impressment, implying that although sailors tried to avoid it, mariners accepted it as part of their livelihoods, and therefore didn’t necessarily have a low morale. Perhaps Johnson is being too generous to impressment here however, as whilst many Africans (mentioned earlier) seemed to seek refuge in impressment, Europeans compared impressment to slavery. Pepys himself, in charge of expanding impressment in the navy in the second and third Anglo Dutch Wars expressed regret at the tyranny that was impressment, on seeing sailors imprisoned and awaiting transfer to ships he wrote of their families ‘Lord, how some poor women cry’.

Although impressment seems to have been most prominent in the eighteenth century, and began to be harshly debated after the Napoleonic Wars, impressment rose to prominence in the first, second and third Anglo Dutch Wars (1652-1654, 1665-1667, 1672-1674). Although impressment was illegal in the Dutch Republic (explicitly at least), the Dutch made exceptions for prisoners of war, who were forced to fight against their own countries, this is essentially because during the Anglo Dutch Wars each side required as many as 30,000 men at any one time, meaning that they required as many seaman as they could find.

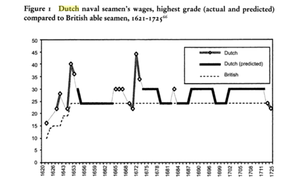

As one can see from the graph above, Dutch wages are consistently higher than British wages, which is why, as Little writes, British sailors impressed into the Dutch navy might not necessarily have too many qualms about fighting with the Dutch navy.

Although there is evidence of the Dutch forcing men into the navy by trapping them in debt, impressment was officially illegal there. This is because, due to their immense empire, they were able to bring immigrants in to work in their navy from countries such as Dutch Brazil rather than have to rely on a brutal and immensely unpopular act such as impressment. This is also prominent in other European nations such as Portugal, who were heavily reliant on their East African colonies for seamen. In the seventeenth century the British Empire was still comparatively small next to the Dutch and Portuguese empires, which meant that the British could not rely on sailors from their colonies, and so had to use impressment.

The Dutch having made it illegal to impress sailors found recruitment extremely difficult, which may go some way in explaining the success of the British in the First Anglo Dutch War, in spite of the successful maritime history of the Dutch. This also explains why the Dutch were forced to have much higher wages than the British, shown in the above graph.

Little writes that the especially in the First Anglo Dutch War, the British had serious difficulties with sailors fleeing their ships, however as Brandon and Fatah-Black argue, this is not strictly due to impressment alone, but also simply out of fear of death, terrible conditions or homesickness, this mean that the situation was no more serious than in other European countries such as the Dutch Republic who did not enforce impressment.

Bibliography

Costello, Ray Black Salt. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2012,p. xvii.

McLynn, Frank Crime and Punishment. London: Routledge, 1989, p. 61.

Brandon, Pepijn and Karwan Fatah-Black ‘For the Reputation and Respectability of the State’.In: Building the Atlantic Empires, Boston: BRILL, 2015,pp. 84-104.

Davies, J. D. Pepys Navy: Ships, Men and Warfare. London: Seaforth Publishing, 2008, p. 112.

Fury, Cheryl A. Social History of English Seamen. London: Boydell Press, 2011, p. 273.

Denver, Brunsman ‘Men of War: British Sailors and the Impressment Paradox’. Journal of Early Modern History, 14 (1/2), 2010, pp. 9-44.

Little, Andrew R. ‘British Seamen in the United Provinces during the seventeenth century Anglo Dutch Wars: the Dutch Navy – a preliminary survey’. In: Brand, Hanno Trade, Diplomacy and Cultural Exchange, Torenlaan: Uitgeverij Verloren, 2005, pp. 75-92.